Author: Ken Gray

Editors: Diane Bull & Margaret Remilton

|

Abridged Story |  |

Full Story |

The first volume of this history focuses on Noel Wood who was the most well-known and influential of them in the art world and was the magnet that drew so many artists to these islands. His works are included in more key collections than the other island artists of the district. Additionally, much more has been written in the press about Noel Wood than of all the others put together. Noel used Bedarra Island as his home base for 60 years and is a district icon.

INTRODUCTION

Artists were attracted to the pristine tropical environment and the isolation of Bedarra, Timana, and Dunk Islands, located near Mission Beach. In the 1930s, several visited, and some stayed. Most notable among the early arrivals were the modernists Noel Wood (1936) with Yvonne and Valerie Albiston nee Cohen (1938). They were joined by Deanna Conti in 1965 and Helen Wiltshire stayed a while from 1975.

Noel Wood and the Cohen sisters stayed during World War II and in 1942, Dunk Island was seconded by the RAAF for a radar station. No visitors were permitted, which meant the three resident artists could paint and explore the islands uninterrupted.

The first volume of this history focuses on Noel Wood who was the most well-known and influential of them in the art world and was the magnet that drew so many artists to these islands. His works are included in more key collections than the other island artists of the district. Additionally, much more has been written in the press about Noel Wood than of all the others put together. Noel used Bedarra Island as his home base for 60 years and is a district icon.

There is much information about his life in newspapers and other records. During our research, we heard that a biography was written (but not published) some time ago and maybe that will surface one day and add further intrigue and detail.

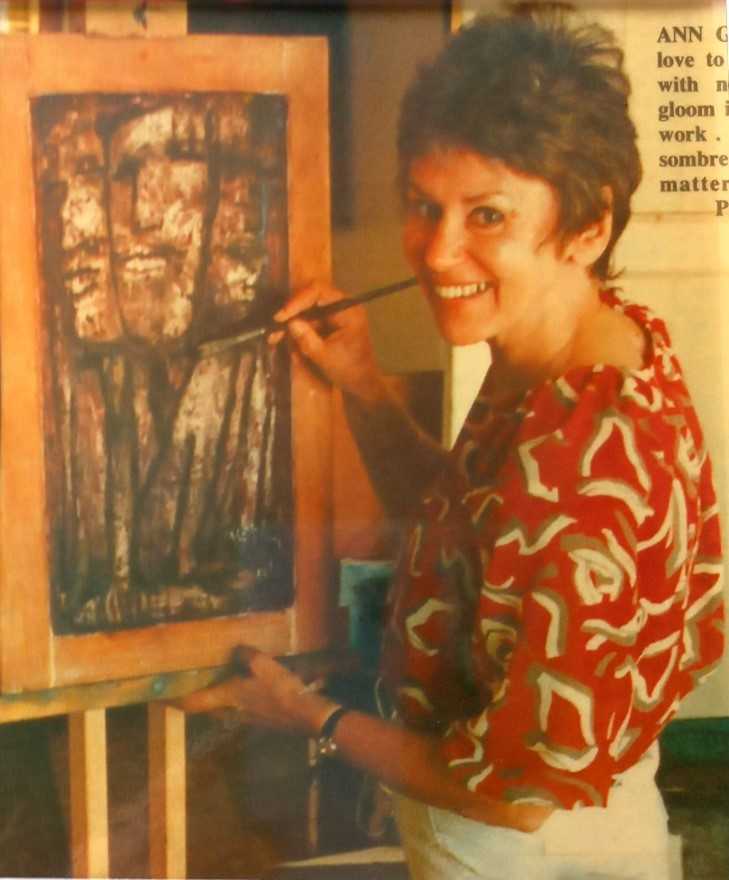

His younger daughter, Bundaberg author and artist, Ann Grocott, provided the richest vein of information on the life of Noel Wood. Rather than blending her memoirs with reports from others, we presented Ann’s words separately. The result is a mix of Ann’s emails and researched history from other sources.

What is apparent, even to someone with no art education, is that visual arts are, like all art, better appreciated by people with knowledge. In music, for example, the most untrained ear can instantly enjoy Beethoven’s violin romances. However, it takes much more time to appreciate Ludwig’s sublime last five string quartets. Take that a few steps further, to Arnold Schoenberg’s atonal music, and this author remains mystified and utterly unable to appreciate that art as many others do. The author, therefore, merely captures what better-qualified people say on matters such as the merit of Noel’s art.

Peggy MacIntyre[1] in 1939, neatly described the dilemma this presents for an artist who relies on selling their art to make a living, as Noel Wood always did:

Perhaps it is an unenviable position for so young a painter to have enjoyed such an extraordinarily wide success. If he goes no farther than he has gone (though this seems unlikely) he will experience the tragedy of portraying picture-postcard problems of the tropics to the complete satisfaction of the tourist, without meaning to do so. On the other hand, if he advances he will lose the support of the larger public in favour of a smaller, more advanced group. At the moment, he stands in the extraordinary position of pleasing nearly everybody.

A few of Noel’s paintings are shown in this story, yet the best of his works sold quickly and are now spread across the globe in private collections so are not available to share.

THE ESCAPEES' HIDEAWAY

The three islands that the Escape Artists lived on are part of the Family Islands in North Queensland:

Image courtesy Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Family Island Group. © Commonwealth of Australia (GBRMPA) 2019.

The image below gives an idea of their relative size. All are forest clad so are ideal as artist havens. Dunk Island land is mainly owned by the State as National Parks and only 15% freehold whereas Timana and Bedarra are entirely freehold land.

Some of the many islands in the Family Island group. Image copyright © Lincoln Fowler Photography, Brisbane.

Some of the many islands in the Family Island group. Image copyright © Lincoln Fowler Photography, Brisbane.

BEDARRA ISLAND

Bedarra Island is a small island of 100 hectares area with permanent water. This was the haven selected by Noel Wood in 1936. Noel owned 15 acres of land on the peninsula where Doorila Cove is.

Bedarra Island, from Google Earth

Noel and his wife Eleanor turned up in their Model T Ford in 1936, found their way to Dunk where Jack Harris, the island owner at the time, was living and purchased the 15-acre lot instantly on seeing it. The Woods started their life on Bedarra soon after buying the land.

Doorila Cove, Bedarra Island, home site of Noel Wood.

Noel named the beaches on the island and built his temporary hut beside beautiful Doorila Cove. Banfield in his fourth book, Last Leaves from Dunk Island, described this tiny, incredibly beautiful beach as only he could:

A little bay lies open to the turbulent south easters, yet lacks not a sheltering cove wherein a small boat may nestle. The cove is formed by a bold and rounded mass of granite, on which pandanus palms and straggling shrubs find a footing. The boat rounds the sturdy rock, revealing a white beach, the sand of which has been ground to such a singular fineness that it feels as silk underfoot ….

From a low pinnacle of rock, on which an osprey is fond of perching, the virtues of the wider scene are best revealed. Five islets, wilderness of leafage, trip out to the east. A mass of fantastic rocks, round which confusing currents swill, intercepts the fairway and beyond the islets are the Brooke# Group, with Goold Island and Hinchinbrook to the right to complete the picture …

Few visit the spot. All its charms are held in reserve.

TIMANA ISLAND

This is a small island of merely 16 hectares with no permanent water supply.

In 1938, Valerie Cohen, after an unhappy love affair, travelled by train as far north as she possibly could and discovered Timana, then owned by Dr Bernardos Homes. Yvonne was immediately summoned to join Valerie on Dunk Island as a guest of Hugo Brassey. They purchased the island and stayed on Dunk while their house was being built. That took three weeks.[1]

They built rainwater tanks and most years stayed on the island during autumn, winter and spring, and took a four-day train trip back to Melbourne to live there for the steamy monsoon months.

DUNK ISLAND

Englishman, Hugo Brassey owned most of the freehold land on Dunk Island when Noel and Eleanor Wood arrived.

Hugo and his wife Christa built a small resort on Dunk that opened in July 1936. Spenser Hopkins, the previous owner, retained 2 hectares of land on Dunk. Hugo enlisted with the Royal Navy in 1939 leaving locals to run his farm and resort and in late 1942, the RAAF built their radar station there.

BEFORE BEDARRA

Noel Herbert Wood (1912 – 2001) lived to almost 90 years of age and spent his first 24 years in South Australia. For 60 years, he was based at Bedarra Island, before living in North Queensland in several places on the mainland for his last few years.

Noel was born in 1912 in Strathalbyn, South Australia and was the fourth son of Reverend Tom Percy Wood (1880 - 1957) and Fannie (née Newbury, 1880 - 1969). He was educated at the South Australian School of Art in Adelaide with his older brother, Rex (1906 - 1970), where he was tutored by Marie Tuck and Leslie Wilkie who regarded Noel as an accomplished portrait painter. However, Noel usually preferred to paint landscapes. He had a short stint in Melbourne where he modelled for Vogue.[1] At art school in 1933, he met and married Eleanor Weld Skipper when 21 years old and they had two children, Virginia and Ann.

Soon after marrying, the couple lived on Kangaroo Island in South Australia in his brother Dean’s house there. He was successful early in his career so his paintings were soon in high demand and sold quickly, and after his first three solo exhibitions in South Australia, he was able to buy a used Model T Ford.

|

|

Noel and Skip, Parramatta Sydney 1936.[1] With daughter Virginia at Dunk Island 1937; both images courtesy of Ancestry.com.au

Life on Kangaroo Island was happy, and the couple had a Clydesdale and would pack up Noel’s painting gear and walk miles to Christies Beach. They broke in horses and hunted kangaroo for food and made their own bread, so were semi-self-sufficient. Dean Wood needed his Kangaroo Island home back, so Noel and Eleanor travelled north in search of their own island in their Tin Lizzie in 1936, eventually finding and buying 15 acres of land on Bedarra Island. Before they found Bedarra, they looked at several locations and stayed for a while on Havannah Island in the Palm Island Group near Townsville.[1]

EARLY DAYS ON BEDARRA

There are differing opinions on the date that Noel and Eleanor came to Bedarra. James Porter was definite, saying it was in June 1936 that they purchased the land and July when they landed to stay. However, Noel’s daughter, Ann Grocott, says they came later in 1936 and she provided the land title dated 24 December 1936 as evidence (see page 19.) The title deeds may have been registered later though, so we cannot be sure what date Noel and Eleanor first settled on Bedarra - it was certainly in 1936.

On the island, Noel and Eleanor quickly set up gardens and imported some goats and chickens aiming to be self-sufficient. At the start, it was sometimes difficult to survive, but he had no problems after adopting permaculture 50 years before the concept was well known. They erected a hut from grasses to provide some rough shelter until he built a small sturdy abode using eucalyptus logs as posts.

Grass Hut built on Bedarra Island by Noel and Eleanor Wood, image courtesy Ann Grocott.

Noel built fish traps and augmented their diet with rock oysters, coconuts for milk and butter and a good variety of fruit and vegetables from his gardens. There were few coconuts available initially as there were only three coconut palms on the island when they arrived, probably planted by the first European owner of the island in 1913, Captain Allason. Noel sourced coconuts from the palms Ted Banfield had planted on Dunk Island and grew them on Bedarra as a food crop.

Eleanor was with Noel for just two weeks before returning to Adelaide for Virginia's birth. Noel was left alone with his fox terrier, Louise, two goats, six hens and a rooster. On New Year in 1937, Noel’s mother visited Bedarra and by then he had the home built and the garden flourishing. Eleanor returned with Virginia later in 1937, after being away for some time and Virginia was soon crawling after they returned. After a marital spat though, according to James Porter, Eleanor fled leaving Noel with Virginia for a period on the island and he fed her on goat’s milk and mashed fruit.[1]

By 1938, Noel had built a bamboo water pipe from the nearby spring to his house, and he was starting to find some time to paint. He was productive and by early 1939, had over 50 good paintings completed for his first exhibition in Sydney. Their second daughter, Ann, was born in South Australia in 1938. At the start of 1940, Eleanor, Virginia, and Ann evacuated the island to be safe from the war and settled at Woodend in Victoria. They did not return until Ann started visiting Noel regularly from 1964 on.

A magazine correspondent later reported that Eleanor Wood did not stay on Bedarra Island because she did not love the life there as Noel did. Nothing could be further from the truth. Eleanor was a capable author and was published in the press on at least two occasions. Her 1937 article, Summer Comes to Bedarra: Idyllic Life on Queensland Tropic Isle, demonstrates her incredible ability to adapt to remote life and her delight in her island home.[2] This shows her deep understanding of and sympathy for the natural environment and the comfort and joy she felt living there.

However, the newspapers (and Noel Wood) quickly forgot Noel’s three girls, Eleanor, Gini, and Ann, who were still living on the island in early 1939 and portrayed Noel as a mysterious, handsome bachelor. That sells more newspapers. And paintings. Eleanor stood no chance against those odds.

One can only conclude that it was Noel’s choice that Eleanor and her children did not return. They divorced later.

Noel’s island life was often featured in newspaper articles in romantic tones implying that life was easy, yet he worked long hours doing gardening and maintenance and painting pictures. Journalists sometimes referred to him as, The Robinson Crusoe Artist and said that he was a recluse, yet while he enjoyed the solace of island life and the peace it provided to focus on his art, he encouraged visitors to his refuge and, from 1940, shared the island with several others.

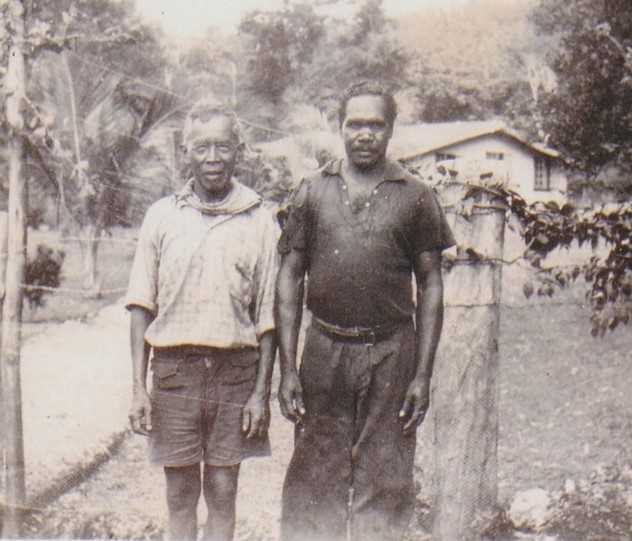

Charles and Mick at (Banfield) bungalow gate, Dunk Island c. 1938. Charlie, Dunk Island c. 1938

Ann Grocott recalled her mother’s feelings about Charlie Malay, the gardener for Banfield on Dunk Island and then for Brassey.

She was very fond of him as was Dad. I have some photos of Charlie taken by Mum.

Mum wrote on the back of the picture of Charlie, “Half Aboriginal, half Malay, Charles once worked for Banford and used to be a cannibal – he still remembers the ‘nice, juicy, sweet flesh of long pig’, one of his Chinese half-brothers.” Mum took all this in her stride without offence or alarm.

In the 1930s, Noel enjoyed the company of Hugo and Christa Brassey on Dunk Island and had a long-term relationship with Hugo after Christa divorced him in 1938. From 1938 until 1965, Noel also had fellow modernist artists, Valerie and Yvonne Cohen, living nearby on Timana island for much of the year. Yvonne and Noel shared a close, loving relationship for some time.

THE ARTIST

Search engine Trove provides more than 150 newspaper articles referring to Noel Wood and his art. He was constantly in the news. Many reviews by art critics among these articles indicate a high level of interest in his works and life.

Even as a student, Noel Wood was becoming recognized and attracting wider interest from the press, as these examples in 1932 show:[1]

Rex and Noel Wood the eldest and youngest sons of the Rev. T. P. Wood for sixteen years the Rector of Christchurch Strathalbyn are studying art in Adelaide. Their course includes nine subjects, and at the end of last year they each secured seven credits and two honours. Noel exhibited three paintings in the last exhibition of the South Australian Society of Arts. In the critique appearing in the ‘Advertiser’, two out of the three received special mention.

In the May issue of ‘Homes and Gardens’, there was an account of the Society of Arts Exhibition by ‘Vermillion,’ entitled ‘Among the Artists,’ from which we cull the following: ‘Noel Wood, a very promising young painter, exhibits for the first time three oils. All show nice paint quality, with a good appreciation of tone and colour.’

Soon after graduating, he had his first solo exhibition in 1934 and that was greeted with unbridled enthusiasm in the press:[2]

An interesting collection of oils and lino cuts, comprises the first exhibition of Noel Wood to be opened this afternoon at the Clarkson Galleries by Miss M. P. Harris.

Mr. Wood … has an intense feeling for colour, and most of his pictures are broad and impressionistic, though not unduly so. Two of his portraits are particularly pleasing, and with care he should develop later into a fine portrait painter, his work being fluent and natural and striking rather a new note.

In 1935, yet another solo exhibition was eagerly welcomed:[3]

When Mr. Justice Richards opens Noel Wood’s exhibition of oil paintings tomorrow at the Society of Arts Gallery, people will be attracted by the portraits and landscape, seascape and still life studies.

Some pictures are seen simultaneously, as in a vision. ‘The Yellow Jacket’ shows a wistful girl, reminding us of the poet Keats’ address to his brother George’s wife: ‘Nymphs of the downward smile and sidelong glance.’

By this time, Noel already had a following in South Australian art circles and critic H. E. Fuller of The Advertiser, Adelaide noted that his art had improved considerably on his earlier works:

The exhibition of oil paintings by Noel Wood … comprises much interesting work. Though he is, perhaps, a little more restrained than in his previous exhibition, he still has a predilection for bright and vivid colours and is able to portray Nature in her best moods. The spontaneity that marks Noel Wood’s work is a feature which ranks him above many of his contemporaries many of whom seem to labour over their work too much … His versatility is shown in his range of subjects which include land and sea scapes, still life and portraits...

I may safely predict that we will hear more of this young artist as a portrait painter… His still life subjects are well chosen with regard to colour schemes and accessories.

Peggy MacIntyre appears to have studied and understood Noel’s works and influences better than most:[4]

He confesses that his first inspiration to paint came from seeing a little-known print of the desert painter, Jacovleff, so many of whose works are to be seen in private collections in Australia…

The influence of Van Gogh can be traced through many of these recent canvases. The late Christopher Woods was a romantic influence, while the detailed studies of Cookham landscapes by Stanley Spencer might be prophesied as a certain influence on the next stage of his work.

Noel’s career as an artist was virtually put on hold for the next four years. During those years, he searched for and found a suitable island to live on, had two children with his delightful wife, Eleanor, built a home and created the essential gardens they needed to sustain them on the island. So, he lost four vital years in terms of developing his skills and accumulating a body of artwork. He did some painting in 1937 though for he exhibited four Queensland oil landscapes at the annual Royal South Australian Society of Arts Exhibition in September 1937.[5]

It was to be in 1938 though when his art career was put back on track and he started to produce significant works once again. However, after painting a swathe of landscapes on Bedarra in his familiar early style, he was not satisfied with the outcomes and destroyed them all and started again: he feels that in the oils which he is doing nowadays he presents the sea-gift scene in a deeper and more intimate way.[6]

While a couple of the critics had small misgivings about some of his artworks later in his career, as will always occur, the vast majority of his reviews, throughout his life, were strongly positive. To this point in time, all of his exhibitions had been held in South Australia and he had quickly made his name there but was still unknown in the big cities. His next step, to exhibit at the chicest of art galleries in Australia’s largest and most international city, was an acid test and must have created butterflies even for the coolest of characters in Noel Wood.

If he did worry, he need not have, for the stars aligned that day. He was accompanied by his best friend, the ever-bold Hugo Brassey, owner of Dunk Island. Hugo had swagger. He was quite the Great Gatsby or Paris Hilton of his day and always drew a crowd. Furthermore, Hugo’s aunt was none other than the Governor General of Australia’s wife, Lady Gowrie. Her husband was not just any Governor-General either, he had distinguished himself during WWII and was reappointed so became the longest-serving of Governors-General in Australia. Handy friends to have.

Lady Gowrie turned up to the exhibition in a flourish, joined by a throng of friends from high places and before the show had even opened, Noel had sold a bucket load of the paintings to high society.

When he presented 52 of his Bedarra paintings to this exhibition at David Jones Gallery in Sydney in 1939, the reviews were particularly gushing and unanimously encouraging. He won the admiration of the Sydney art world in a heartbeat and his reputation was made:

Brilliant Paintings. The spectator has a corresponding sensation of strength and assurance. That is what makes this exhibition such a success. Apart from the subject matter, Mr. Wood is a singularly accomplished painter. He sets luxuriant foliage down on canvas in meticulous detail, and he breathes life into it. He is sensitive to the swift atmospheric changes of that tropical climate, and they too find vital expression. The foregrounds of the pictures are always skilfully worked out… And, supremely important, Mr. Wood rejoices in the lush colour of it all – the hard blue shadows; the pale green and dark green; the flat grey of a bay under a rainshower. There is no monotony in the series. Mr. Wood must be set down as one of Australia’s most forceful artists.

Sydney Morning Herald, 01 May 1939.[7]

Noel Wood’s paintings of tropical foliage burst on Sydney with an unexpected freshness and charm when this young artist held an exhibition at David Jones’s during March. … At one bound, Noel Wood placed himself amongst the most interesting of the local artists. … Apart from the novelty of his subjects, Wood is a painter’s painter. His canvasses show individuality, freshness of attack, feeling for design and a decided sense of the pictorial. … For most people this was the first time his name had been heard. Yet the exhibition earned for him a definite and prominent place in Australian art. Peggy MacIntyre, Art in Australia 15 May 1939.[8]

The artist has handled his subjects with certainty and ease, and the treatment of foliage, the suggestion of colour and light, are the main features of his work. He has a sense of composition, and he can dramatize his effects by clever arrangement of shadows. It is refreshing to see an artist of Noel Wood’s ability lifting such subject matter out of the rut.

Sydney Ure Smith, Daily News (Sydney), 05 March 1939.[9]

Lady Gowrie and her notable entourage were not the only celebrities to be seen at the exhibition. The Sun, Sydney, reported on another notable spectator, from Brisbane:[10]

Miss Marjorie Wilson, daughter of the Governor of Queensland (Sir Leslie Wilson) and Lady Wilson who is a keen art student was an interested spectator at Noel Wood’s exhibition of paintings at David Jones’s on Saturday.

Within a few days, Noel Wood had sold eight paintings for a sum of $4,500 in 2022 currency equivalence. The publicity Noel received from this exhibition was incredible with widespread coverage in most major cities across the nation and many regional newspapers also publishing the stories. The press was having a field day and even the popular social-gossip magazine, PIX, published a two-page picture spread of Noel Wood and Bedarra.[11]

From the chat in The Sun, Sydney, it was clear that word spread quickly about this exhibition and the handsome, mysterious Noel Wood was a magnet for young ladies and confident in his approach:[12]

What is it about a young man that takes himself off to live alone on a tropic island away from the rest of the world … away from the hair-oil, cocktails, boiled shirts and tramcars?

Whatever it is, artist Noel Wood has it … and as might have been expected, a whole host of pretties rolled up to see him opening his exhibition of paintings of The Barrier Reef … David Jones’s … on Friday.

The opening was a good one … best people and all that. And the red spots on the frames indicated that they hadn’t only gone to look as is the sad story of so many art shows.

Noel Wood stuck to his unconventional ideas and refused to stand alongside the show opener while she said nice things about his pictures.

The rest of this long article told of Noel’s life alone on his romantic tropical island. No mention of Eleanor Wood or Gini and Ann.

In May 1939, Noel went on to test his mettle in Melbourne with an exhibition in Riddell’s Galleries. He had far fewer paintings to show yet news of the artist had spread quickly and Melbourne was ready for another blockbuster art show. The Herald, Melbourne and The Mail, Adelaide ran the same extensive story, The Man with the Open Door, before this much-anticipated exhibition.[13]

High up in a Collins Street building today, the door to an artist’s studio was ajar… In the room, working on a self-portrait, with the hum of the city almost but not quite shut out, was Mr. Noel Wood …

The door today was a symbol. For where Mr. Wood usually paints, in the tropics, his studio laps over heavily timbered hills and across the blue waters down to the horizon. There is no one to keep out. And nothing to shut in. Tall, brown, and slim, he was surrounded today by some of the striking pictures from the Barrier Reef which will make up the one-man show he intends to open at the end of the month.

His manner of life has been compared with that of the Frenchman, Paul Gauguin, whose hunger for colour drove him to the South Seas. But, as Melbourne people will see, Mr. Wood’s style is quite different from that of Gauguin’s light chocolate Tahitianness.

That exhibition was also a big success, and The Age critic was at first glance unsure but, on reflection, was also suitably impressed:[14]

A first impression on viewing these essays in tropical sunlight is that the shadows show an undue blackness, but on consideration, it becomes apparent that any seeming inconsistency in this respect is due to a condition of light differing in vibration and intensity from that prevailing in southern Australia. The attitude of the artist in making these studies of sunlit vegetation is one of obvious sincerity of purpose. He may be described as a ‘direct impressionist’ inasmuch that he gives us a first-hand impression of certain phenomena of nature set-down tone for tone as he found it, but with an added inspirational understanding of its rhythmic significance.

The Herald’s art critic also picked up the story[15] and explained why he regarded Wood as a promising new talent:

Mr Wood’s painting is almost unknown in Melbourne – or was until two of his landscapes were exhibited in the Melbourne exhibition of the Academy of Art. These two pictures were of outstanding quality heralding the rising of a new star in the artistic firmament. The canvases on view were painted on Bedarra Island, Great Barrier Reef, half of the island being owned by the artist…

In this exhibition, Mr Wood more than justifies himself. While a ‘modern’ in trend he paints sanely what he sees, realising that Nature provides bounteous fare for his brush. Virile painting, and a strong sense of design, are to be found in all the works shown. Mr Wood never descends to the level of the picturesque, nor would any of his pictures do for a postcard. The paint is applied with studied reserve, each tone, however, tells in the general effect, and he knows how to make his paint decorate the masses treated… Mr Wood does not despise tonal truths, nor ignore them, as many ultra modern artists do, realising that colour and tone are inseparable even in formal design.

When two of Noel’s paintings were sent to Melbourne and Adelaide for Australian Art Academy group exhibitions shortly before this, the South Australian press quickly claimed Noel as their own:[16]

The Australian Academy of Art Exhibition of 170 paintings, etchings and pieces of sculpture will be opened in the Adelaide National Gallery next Wednesday … In this article, Norman MacGeorge of Melbourne discusses the works of the South Australian artists in the exhibition… Two extremely vital and powerfully painted pictures are garden scenes by Noel Wood acclaimed by critics of advanced views in Melbourne as the finest landscapes in the show. The catalogue claims Mr. Wood as a Queenslander, though he is from South Australia.

Helen Seager, art critic for Smith’s Weekly, Sydney reflected on his success in her May 1939 article, Artist-Hermit Turns Back on Money, Cities:

In Sydney, last April, he [Noel] held one of the few successful one-man shows in Australia, this year. Some artists say it was the only successful show. He received enough commissions for portraits to keep him busy in Sydney for two years. But he refused them all.

In 1940, Noel held a Brisbane exhibition jointly with Roy Dalgarno which was also enthusiastically reviewed:

Outstanding is Noel Wood’s study of mammoth trees on Dunk Island … There is not a superfluous stroke in the whole picture, which probably constitutes the gem of the show. … Mr. Wood also shows a gracefully poised sketch entitled ‘Yvonne.’

The Telegraph (Brisbane), 04 December 1940.[17]

This study by Noel Wood [‘The Idyll’] whose tropic pictures … have created a sensation in Brisbane, was painted on the Barrier Reef.

The Courier-Mail, Brisbane, 07 December 1940.[18]

Professor J. V. Duhig, President of the Royal Queensland Art Society, opened the exhibition and was interviewed later by The Telegraph, Brisbane:[19]

The professor described the exhibition as a very striking one, most unusual in its extremely vivid colours and excellent technique. Noel Wood, because of his sheer technique alone was worth watching, and he was well supported by Mr. Dalgarno. Will Ashton’s work was the only Australian art that was comparable in style with the pictures under examination, which got away from the post-impressionist style brought to Australia by Sir Arthur Streeton and continued by Hans Heysen and Elioth Gruner. Thus Messrs. Wood and Dalgarno really had introduced a new school which was not yet named but which probably would become known as the tropical school.

Noted Brisbane journalist and art critic, Firmin McKinnon, joined in on the enthusiastic response to this exhibition:[20]

Mr. Noel Wood and Mr. Roy Dalgarno … have captured on canvas the brilliant contrasting colours and the hard intense lights of the tropics.

These essentially tropic features are the keynote of an exhibition of paintings that will be opened … in Prince’s Ballroom… It is the first time that the north has been brought to Brisbane in oils; and it is an opportunity that picture-lovers should not miss seeing, an exhibition that is unusual, original and thoroughly typical of the Far North.

Noel’s reputation as an artist was now spreading quickly, even to his home region, and the Cairns Post joined in the adulation:[21]

Tropical Queensland has waited for a long time for an artist capable of harmonizing its brilliant colours on canvas. It has found him in Mr. Noel Wood. It is unquestionably a break from the conventional art of Australia because Mr. Wood has captured the dazzling sunlight of the North as no other artist has ever succeeded in doing.

He has so thoroughly mastered the lights that one of the most interesting contrasts of the exhibition is seen in the soft lyrical lights of early morning and late afternoon and the blinding blaze of noonday when the sun strikes down with Thor-like intensity.

Within five days, 24 of the artworks had been sold at this exhibition. One of Noel’s exhibited works was acquired by the Australian National Art Gallery, the second Wood painting they now had in their collection.

In 1941, Firmin McKinnon, in another highly positive review declared: Mr. Wood is Australia’s most individual artist of the tropics.

Noel returned to Adelaide to show his new wares and was once again greeted warmly with another strong review by H. E. Fuller:[22]

The exhibition of Noel Wood’s paintings of North Queensland scenery … is a wonderful exposition of the beauty of this part of the world… His impressionable style and technique lend themselves easily to the production of the vivid colouring of the tropics, and the few broad strokes of the brush, which in less capable hands might be meaningless, in his become almost a living reality, more especially as he is careful in his attention to composition and design…

His work is consistently forceful and strong in handling, and one sees no suggestion of hesitancy.

All major South Australian newspapers gave Noel glowing reviews including this (clip) from News Adelaide:[23]

Whatever Robinson Crusoe did on his island, he never thought of painting it, as Noel Wood has painted his half-island, Bedarra … Only those who have tried to paint Nature in an extravagant mood will realise that the pioneer work on the island with an axe and a shovel was child’s play to the hard labour which has gone into the art of the tropics with its rigorous selection and the deceptive simplicity of the artist’s design.

Another art critic, writing for News Adelaide, Palette, chimed in with further accolades:

Mr Wood’s work while it will doubtless awaken storms of derision in the unformed minds of our young ‘moderns,’ is very sincere, very strong and very true. It is also colourful work and a most desirable possession… One does not have to hark back to Streeton, Picasso, Bracque of even Coco the Clown on surveying his efforts. Here is a simple, honest young man who in the course of his daily occasions suddenly sees a cobalt green vista through the palms with a boat from the mainland looming up. “Ha” he says, “This is good. Wait till I get my paints.” … and a lovely work it is. I sincerely hope lovers of art will buy it. We have been regaled with futilities in the shape of art, so that the advent of an honest, uncomplicated man like Noel Wood is balm in Gilead indeed…

Mr. Wood brought this experience home to me [Magnetic Island] vividly, especially in that beautifully handled “The View of Tully from Dunk.” This is exactly what I saw myself, the silver sea against the light, a most difficult subject, but done with unerring grace.

Then, in 1941, one of Noel’s paintings held in the Queensland Art Gallery collection was chosen by an expert panel, to be exhibited in a series of events to highlight Australian Art in Canada and the USA.[24]

In 1943, Noel ventured back into Sydney for another solo exhibition, this time at the Macquarie Galleries and took a bit of stick from an art critic who decided that Noel displayed bull in the china shop methods. Nevertheless, he conceded that one cannot help but like them with all their faults. The critic was writing for the Sydney Morning Herald so perhaps he did not like Noel’s politics (or lack thereof).[25] When this review is compared to the Sydney Morning Herald’s review of Noel’s 1939 Sydney exhibition it is an amazing turnaround for that was possibly the most positive review that Noel ever received. Probably, the paper used a different art critic on this occasion.

In 1944, Noel revisited Brisbane with another solo exhibition at the Canberra Gallery and was declared by Firmin McKinnon[26] to be the artistic master of that country. [the tropics]. The Telegraph’s art critic gave an equally positive review saying:[27]

Art lovers … will find much to interest them. … his land and seascapes and even his still life are redolent of the tropics. It is the tropics painted with a vigorous brush and a virile technique. Here is an artist who is not afraid of colour. He uses it audaciously, yet cleverly, with never a clashing note... The quality of the paintings varies slightly, but values are sound throughout and treatment is invigorating.

Noel joined Yvonne and Valerie Cohen and Charles Martin to exhibit in Melbourne’s Georges’ Gallery in 1945 and the reviews were positive for all four artists. The Age (13 February 1945) declared: Of the four contributors, Noel Wood is the most accomplished. The Argus on the same date stated that Pride of place goes to Noel Wood, whose No. 12 ‘Hibiscus’ is perhaps the outstanding work in the show.

A critic calling himself WEP, and writing for The Daily Telegraph, Sydney found fault with Noel’s new direction in 1946. This was an exhibition held at the Grosvenor Galleries in Sydney:

Artist Noel Wood appears to have fallen between two stools. Some years ago he was comfortably seated on an objective view of the sub-tropical islands of the Barrier Reef. Today he is endeavouring to settle down on a more elusive and interpretative expression of the same places. Although commendable, this manoeuvre is meeting with indifferent success. Wood still lacks the subtlety of vision which could illuminate the goal he seeks. However, control and reticence [in four of his works] in form and colour indicate surer steps along the chosen path.

The Sydney Morning Herald’s critic was partly impressed with the exhibition yet the review had his usual sting in the tail:[28]

The paintings of Noel Wood at the Grosvenor Galleries can be summed up in one word – they have bounce. On the other hand, Wood’s “bounce” to the exclusion of sensibility can be overdone. This, and his limited means, make a preponderance of failures a matter of course… But Wood has also a few successes and he atones splendidly [in many paintings.] … The painter shows talent, but what he requires, above all, is patience.

However, as is so commonly said, art is in the eye of the beholder, and the reviews of Noel’s next exhibition at Finneys Auditorium in Brisbane were, once again, highly complementary:[29]

Noel Wood has already established himself as an artist of distinction, particularly in regard to the tropical scene, and this present exhibition at Finneys Auditorium adds to that distinction… There is a fine restraint about these pictures which enhances rather than detracts from the faintly menacing atmosphere of the jungle which is their background. The exhibition includes a number of still lifes, all of them good.

The Courier Mail reviewer was equally pleased with Noel’s exhibition:[30]

The feature of the exhibition is that the artist has painted his tropic scenes with grace and with a sound and carefully studied knowledge of the effects of light and shade.

In 1947, Noel spent three years in Europe, staying for some time with his brother, Rex, in Portugal and with his close friend, Hugo Brassey, in Ireland. While in London, he painted commissioned portraits to make a living.

American film director, Byron Haskin, met Noel in London and again on Bedarra Island and invited him to work and exhibit in Hollywood. Noel chose not to exhibit yet did a year as an assistant art director in 1955-6.

One of the most negative reviews that Noel Wood received was probably in 1959 when he held an exhibition with his brother Rex in Adelaide. The comments were published by local art critic, Ivor Francis, in Crafers Journal in December 1959 under the title: Ivor’s Art Review. However, Ivor Francis had been somewhat critical of Noel’s work after an exhibition of Noel’s in 1945 where all the other critics were very positive - an artist cannot please everyone. Eleanor Wood recorded his words in a handwritten note to Ann Grocott ending with a comment: I don’t think they’ll care much for this criticism, either of ‘em!

This was one of those specialty exhibitions. The work of the Wood brothers provides each with interesting contrasts. Rex is very much “School of Paris,” delicately cold and nothing if not structural. Noel is romantic, tempestuous tropical and lush. And that almost sums them up. Rex derives most immediately from the coast-scene of Chirico, Noel from the islands of Gauguin; but in both of them expression has become specialist, interpretive and academic. The result is pleasing, well-designed pictures to hang on a wall rather than residues of creative fires to be pondered over.

Noel commonly showed 50 or more paintings at his solo exhibitions. In Trove and Design & Art Australia Online,[31] a quick search uncovers at least 15 solo exhibitions held in major cities and some of these went on to be shown in many regional galleries. At the peak of his powers, in 1947, he sent 50 of his finest paintings by rail to Sydney for an exhibition he planned there before taking some to England for an exhibition at Leicester Galleries in London.[32] However, these were all lost in transit and never found.

Noel’s works were commonly featured in group exhibitions and 18 of these events were found in the literature, including an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1941, a series of Queensland Art Gallery exhibitions held in the USA during 1950 and the Queensland Artists of Fame & Promise exhibition held in Brisbane in 1953.

His works are owned by at least nine important Australian galleries including the National Art Gallery in Canberra and the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) in Brisbane. Galleries in Brisbane, Melbourne, Adelaide, Armidale, Cairns, Townsville and Bundaberg have one or more of his works in their collections.

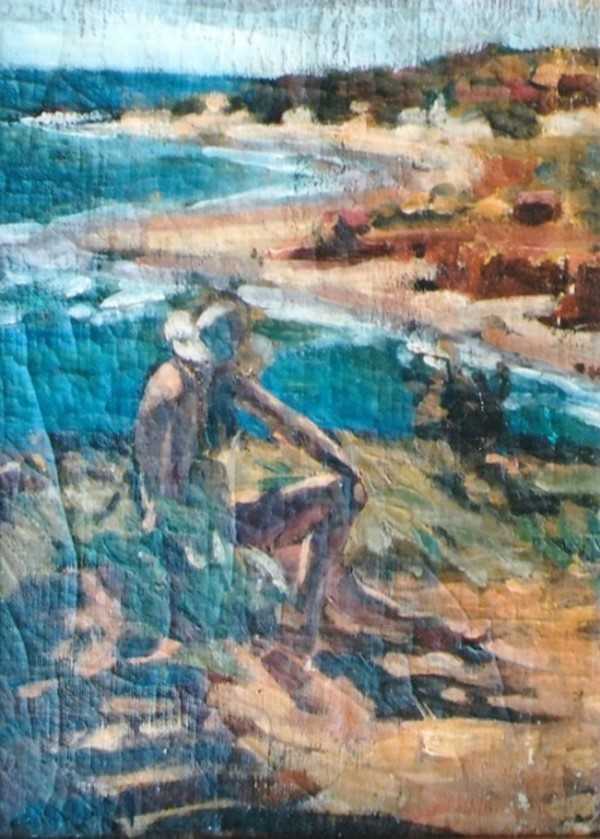

Noel WOOD/Australia 1912-2001/ The pathway to Banfield’s old home (Dunk Island) c. 1940/ Oil on canvas on composition board/ 46 x 59.8cm/ Purchased 1940/

Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art/ © QAGOMA/ Photograph Natasha Harth, QAGOMA

Noel WOOD, Still life – the kitchen table, oil on board, Australia & New Zealand Art Sales Digest.

Because almost all of Noel’s paintings were sold at his exhibitions, they are largely held in private collections and do not come up for sale often. In 2019, Ross Searle stated that only 12 of Noel Wood’s works had come up for sale since 2007 and the prices were $3,000 - $4,000.

At an auction by Leonard Joel in Melbourne in 2019, 59 of Noel’s paintings from a deceased estate were catalogued for sale. Ann Grocott immediately raised the alarm demonstrating that at least 16 of these paintings were fakes. She had owned the originals for many years including some of those offered for sale. Ross Searle owned one that had been copied as well and said six of the paintings for sale were held in public collections. The 16 suspect works were removed from the auction.[1]

In musical history, some composers such as Schubert and Mozart were able to write music quickly once a thought entered their heads and they seldom tinkered with work after it was finished. Others, like Beethoven, took much longer to complete their works and often returned to the composition over a long period of time to polish it. The same applies to artists. The extreme is perhaps Leonardo who never completed some of his best works and did not release them if he felt they needed more polishing, even when they were commissioned pieces.

Noel Wood was a Schubert not a Beethoven or Leonardo in that respect. He was never one to ruminate about his art or style and you seldom heard him speaking of his art when he was interviewed. He was certainly not self-absorbed or lacking in humility.

On one rare occasion, when Noel spoke of his art, he said that being remotely located gave him the necessary time to think about his paintings. Hence, the suggestion by one critic that he was a bull in a china shop, was possibly unfair criticism. He did plan his works and most critics found he was sound in his design and planning.

It is impossible to separate the man from the artist. They are intertwined. Noel Wood’s philosophy of life was simple and clear from early in his life. He adopted a form of Zen Buddhist philosophy and was not at all religious. Awe of Nature was probably the closest thing to religion Noel had. No gods seemed to have invaded his thoughts.

His philosophy impacted his art, for he had no concern whatsoever for what others on the planet thought of him or his work. He loved to paint and set his own agenda and if his style changed over the years, the evolution was driven by Noel alone. He was not focused on what critics said at all. His philosophy was to live in the present and he openly declared that he did not wish to be remembered. He was not influenced by what the world would say about his art when he was dead.

A few critics spoke briefly of how Noel Wood was evolving as an artist. Peggy MacIntyre’s early assessment of where Noel Wood stood in his development as an artist made much sense to a layman.[2] Peggy concluded, not surprisingly, that at that stage (age 27 years) Noel was able to please both worlds – the casual uninformed appreciator of art who sought an attractive picture and the sophisticated art connoisseur seeking art with deeper or hidden meaning.

In 1959, critic Ivor Francis, suggested that Noel could not take the leap from producing pleasing, well-designed pictures to hang on a wall to producing residues of creative fires to be pondered over. Ivor concluded, therefore, that in his eyes, Noel failed the ultimate test of an artist. Noel had to sell his paintings out of necessity. He could not afford to go too far toward a purist’s expectations of art for fear that sales would dry up.

How you determine with certainty that a painting has deeper meaning is not an exact task; perhaps that is why we call it art, not science. It would, I presume, take a panel of art experts to examine a significant number of Noel’s best works to determine where he stood on the sliding scale of postcard versus mysterious visual poetry. Noel Wood’s works are spread across the globe and not easily accessed so it would be a difficult or near-impossible task now.

However, many experienced art curators and critics published critiques of Noel’s works over the years and the consensus appears to be that he was a significant Australian artist. Further, the number of his works that found their way into important public and private collections would indicate that his art is ranked quite highly. As we demonstrated earlier, some art curators believe the work of regional artists such as Noel Wood has always been under-recognized.

The research revealed in this small publication will hopefully give readers interested in relativity sufficient access to information to form their own view of Noel Wood’s position in the art world.

But, if Noel is watching, he will not be at all concerned about what we conclude! He will probably just giggle inwardly at our seriousness and think to himself that we might try to be a little kinder.

BACH & BANANAS - THE MAN

On 26 May 1956, an interview with Noel Wood was published in The New Yorker and this offers us some candid insights into Noel’s life and motivations. The article’s title was Bach and Bananas.[1]

Our brave new acquaintance is an Australian named Noel Wood, who has been paying his first visit to New York. A tall, dark-haired, and charming man of forty-three, Wood is the sole inhabitant of a tiny island called Bedarra, which is seven miles off the coast of Queensland, inside the Great Barrier Reef.

He has lived on the island for nearly all of the past twenty years and will head back there after looking up friends in Hollywood, New York, London and Ireland. ‘I first went to Bedarra when Mussolini was mopping up in Abyssinia, or trying to,’ Wood told us. ‘My reason was a simple economic one. I was making a living as a portrait painter in Sydney and hating it. I decided to find a place where it would cost absolutely nothing to live, so I could paint as I pleased.’

‘People ask me if I get lonely,’ Mr. Wood said,’ ‘The answer is no.’ ... ‘Now and then I go on painting jags during which nothing matters except my work.’ .... ‘Once, a writer and his wife and two children arrived unannounced and stayed a year. He wrote a book about the experience and described me as ill-tempered - do you wonder? I’ve got an inordinate amount of reading done on Bedarra. … My favourite is Pepys. I read at night, with the help of a kerosene lamp. I’ve a windup gramophone, and I assure you that the still night-time jungle is the best place in the world in which to listen to Bach.’

‘I’ve invented a sort of flat beer made out of coconut buds, and a light white wine made out of mangoes and pineapples. I’ve never been sick a single day on the island.’

Noel Wood, 1939, Pix Magazine.[1]

Further insights are gleaned from fellow artist, Roy Dalgarno’s recollections of his time together with Noel Wood in 1940. Roy met Noel around 1930 in Melbourne when they were both students. In 1940, Noel invited Roy to Bedarra, and he stayed there for five months before they jointly exhibited 60 - 70 of their works in Brisbane. The exhibition was a resounding success with many paintings selling and the critics reviewed both artists in strongly favourable terms.

Roy loved life on the island, and they worked well together on Bedarra and at exhibitions. In an unpublished autobiography, Dalgarno spoke joyously of their escapades, The island had no jetty, so we jumped over the side with our supplies and waded ashore.

However, after the exhibition when Roy eagerly planned to return to this life on Bedarra he struck a snag. Security would not allow him to return while the war was on:[1]

When I arrived at Tully, Noel met me at the station. He’d been back about a month and I could see immediately that some problem had come up. ‘Look Roy, I’ve got some bad news. I’ve been told by the police not to allow you back on the island.’ I couldn’t believe this. …. The intelligence people had instructed Tully Police Chief, Sergeant Schmidt, not to allow me back on the island. Noel explained to me if I kept on living on Bedarra they would close him up; they wouldn’t allow him to live there even, because they said it’s a sensitive security issue. They’d apparently planned on building some sort of military establishment there and they considered me a security risk. A security risk? Because I was a Communist or a member of the Left Book Club. I was confused and devastated to have my island life terminated. All I thought to say was, ‘Jesus Christ, what am I to do now?’

Noel of course was terribly embarrassed. He couldn’t stand to have his idyllic life disrupted. After a while, I appreciated his situation there. … he was faced with a fait accompli by Sergeant Schmidt. He managed to remain there during the war and wasn’t called up for service as they normally would have. He decided to grow tomatoes there for the war effort and was allowed to stay. Noel, being a very conservative chap, … [was adamant about] protecting his Shangri-La from publicity.

I never saw Noel after that. We never corresponded, although I had left my art books and many personal things, some preliminary sketches, and clothes, on Bedarra island. I was so disgusted and depressed about the whole affair and returned to Brisbane that same evening after a few farewell drinks at the Tully pub, but it was a most uncomfortable farewell for both of us. I wasn’t even permitted on the island to collect my things. He may have been unfit for military service even—I never knew. We hadn’t fallen out in any way. He was clearly pressurised. Noel was completely apolitical so it would not have occurred to him to take a political stand.

So much for the Garden of Eden.

Ironically, soon after, Roy joined the Camouflage unit of the RAAF, working in North Queensland, including some of the islands, until the end of the war. Ann Grocott explained that her father was only 27 when war was declared but was a haemophiliac and suffered from emphysema, so he was allowed to stay on the island and grow fruit and vegetables for the war effort. On reflection, Ann added: I am sure that he endured lung problems and was always told that he bled a lot when he was young but I did not ever confirm with him that he was suffering from haemophilia so that may not be so, yet his health was marginal in many ways.

Another publication reveals a different side of Noel’s life on Bedarra in 1940 when island conflict was the everyday norm. Oddly enough, this story does not mention the presence of Roy Dalgarno on Bedarra that year. This is the largely autobiographical book, written by Guy Morrison, We Shared an Island.[2] Guy was a journalist who met Noel in Brisbane shortly after his successful exhibition at the David Jones Gallery in Sydney, in March 1939.

Guy’s version of events differs considerably from Noel’s version spoken of briefly in an interview with the New Yorker in 1956. Guy says that they met three times in Brisbane within a few days. Guy and his wife, Kay, were entranced by Noel’s stories of life on Bedarra and decided that they must leave Sydney and join Noel as soon as possible. Guy says they corresponded several times before heading north, and that Noel was keen for them all to come and join a colony at Bedarra. Ultimately, Noel saw the Morrisons’ visit as an unwelcome surprise and he was immensely relieved when they eventually left the island.

John Busst, who had met Noel Wood a little earlier in 1940 at Monsalvat, an Elwood commune he lived in, was with Noel in Brisbane when Guy met Noel. Busst too had been amazed at the wonderful tales of Bedarra and was on his way there to stay. He had this idea of having a colony or commune on the island and had sold Noel on the concept of many hands making light work.

Noel was, by 1940, increasingly aware of the penalty an artist paid for living on a remote tropical island. It was hard work maintaining the property and generating enough food. Busst spoke of his experience of life in the commune and how Noel would do less manual work and more painting if he gathered a small group of like-minded people on his island.

Noel WOOD, Montsalvat, 1940, private collection.

This grand plan quickly turned to custard when it was enacted with little thought. Busst arrived on Bedarra with Noel and started to set himself up on land he leased on the southern end of the island. He came with his builder and was hell-bent on building a substantial mud brick home. That concept was entirely alien to Noel; that was not what he envisaged for the island at all. To Noel, that was bringing some of the world’s worst evils onto his island.

The relationship between Wood and Busst quickly soured and never really recovered. On top of their differing views on how to build and live, they initially fought over a girl living on Dunk Island and after Noel had been seeing her for some time, John Busst horned in and started rowing to Dunk and seeing her secretly as well. Both men loved the company of young women. Busst had inherited a fortune when his father died and had the cash to do whatever he wished.

In April 1940, during an extended monsoon season, Guy Morrison, his wife and two young children landed on a beach at Bedarra full of optimism about their new life in Eden. They had no belongings with them and no money and for the first month, Noel’s tiny ‘house’ somehow had to cope with seven inhabitants (Busst, his builder, Noel and the four Morrisons.)

The story tells of an unrelenting war of words and frustrations between all parties on the island and the acrimony intensified when two wealthy men (Pierre Huret, a Frenchman and Dick Greatrix, an Englishman) purchased the entire land on Bedarra but for Noel’s 15-acre lot. Guy called these people the rich Americans. It was to be a year that Noel Wood deeply regretted encouraging people to come to stay in his piece of paradise. He lost his precious private space and time. However, while it is not relayed in this book, Noel still invited an accomplished artist, Roy Dalgarno, to stay that year and that relationship worked well for the five months they were together, perhaps based upon mutual respect for one another’s art.

Early in Guy Morrison’s tale, we learn that while Busst and Wood were hatching their hasty plans for a commune they were both constantly fuelled by their heavy alcohol consumption. Busst was an alcoholic and Wood was probably sailing close to that breeze as well. We see from the records that there was a pattern in Noel’s life, with him sometimes making statements or promises while in a drunken state and then bitterly regretting the words later.

Noel Wood loved fun and the company of others and made friends easily, yet he also craved privacy and valued time alone to paint, muse and enjoy his own company. He got along very well with socialist, Roy Dalgarno yet struggled to form a bond with John Busst who he said (to Guy Morrison) was a lousy painter but a good drinker. John Busst stayed on Bedarra nonetheless, leasing part of the land until 1947, when he purchased most of the island. He married in 1950 and left Bedarra in 1957 and Noel was seldom with the Bussts in their last seven years on Bedarra.

Later, to enable visitors to the island without the same unfortunate side effects, Noel built an art studio for himself well away from his house, near the spring. He also built a small conventional guest house on the opposite side of the island at Coomool Bay, to reduce the adverse impacts of visitors.

In the early 50s, while Noel Wood was in Europe and the USA for three years, Busst decided that Noel’s informal land title would not stand up to legal scrutiny, so he could claim it as his own property. He took the case to court in a sadly opportunistic moment, but Noel won anyhow. The relationship, such as it was, deteriorated badly after that incident no doubt.

Noel’s artist’s studio.

In newspaper interviews, Noel often said how much he disliked the way the world was. He was largely apolitical yet railed at the way most humans lived their lives. He could escape that best when he lived remotely and, while he said he was not an escape artist, that seems to an observer to be exactly what he was. He often described the world as being mad and his island was his refuge from that. He said, for example, in The Courier-Mail, in 1940, I am not an escapist. I have worked out satisfactorily how I can live happily in this mad world without worrying anyone.[1]

In the same newspaper article, the correspondent captured some words from Noel on his life on the island:

Noel Wood loves cooking. He has a book called ‘Recipes of all Nations’, by Countess Morphy. The West Indies recipes suit Bedarra perfectly, ‘I could serve you a magnificent dinner in my hand-made bungalow,’ he said. First, there would be oysters if you get them yourself. Then you could have gungamurry fish. This is an abo (sic) dish – you wrap the fish in a banana leaf and cook it in the ashes. Then you could have chicken and sweet corn cooked in a coconut. You chop up the chicken and seasoning, remove the top of the coconut, fill it, place the top on and steam or boil. It’s wonderful. For vegetables you would have corn, kasava and spinach tops, with Chinese long beans, taro and sweet potatoes cooked in jackets. For dessert, crystallised fruit. (I’m pretty good at that and fruit in season.’

Of course, the meal would be served on tanagara leaves as Noel does not like washing up. These wonderful leaves are just as good as china – except for soup. The artist rises at daylight and has a swim. Then he has the sort of breakfast you or I would have – eggs, fish, fruit. After breakfast he paints. And when he has had enough of that he improves the property.

However, he did not dislike the world so much that he curled up and hid on his island. In 1947, he went to London, Ireland and Europe for three years staying with friends and painting commissioned portraits to make a living on the road. He stayed for an extended period with Hugo Brassey in England and Ireland. He painted landscapes in Ireland and France and met and linked up with journalist, Joyce Lambert in Paris. The couple returned to Australia where they ran Hugo’s resort for two years.

Noel WOOD, Cagnes France c. 1948, private collection.

In 1955, Noel took up an invitation from film director, Byron Haskins to work for him as an assistant art director in Hollywood. Joyce split from Noel at that point and went to work in New York. Noel had met with Byron on his previous trip while in London. Noel stayed in the director’s role for a year working on a TV series, Long John Silver. He then stayed with his brother, Rex, in Portugal for a time then returned to Ireland to stay again with Hugo. After three years abroad, Noel was back to Bedarra and this time it was to stay.

James Porter, in his excellent account of Noel Wood’s life in his book, A Family of Islands, explains how much his garden meant and how immaculately he maintained his home, paths and gardens. By the 1950s, the home was still open to the forest in many parts, yet it was well-built and decorated for gracious living. Noel kept a large library of books that he shared enthusiastically with his visitors who found he had a near photographic memory and remembered large swathes of text easily.

He did not read newspapers yet subscribed to a couple of magazines like The New Yorker. He had no radio until late in life and spoke of not knowing of King Edward VIIIs abdication in December 1936.

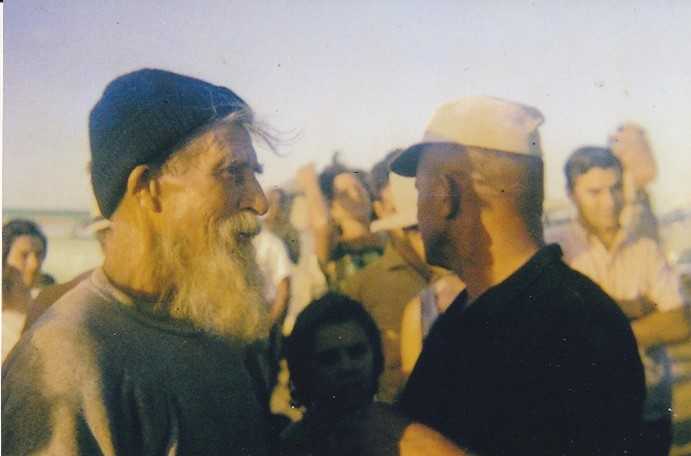

In 1983, correspondent Michael Fessier Jr and photographer, Katherine Holden from International Islands Magazine, visited Dunk, Timana and Bedarra Islands and published an extensive article titled, On the Road to Mehetia, which included interviews with Bruce Arthur, Deanna Conti and Noel Wood.

They arrived unannounced and spoke of their meeting with Noel at Doorila Cove.[1]

There on the beach stood a bearded character wrapped in a bright cloth of South Seas pareu, and looking as if he’d been expecting us – although there was no way he could have known that we were coming.

Geoff dropped anchor a few feet off the beach, and I waded ashore behind him, There was no surprise at seeing us in the bearded man’s manner; he managed a perfectly balanced mixed greeting, genial and pleasant with a certain built-in and absolute limit.

When Geoff mentioned my name, the bearded man smiled and said affably, “Yes, I knew your father.” … The bearded man had been a prominent Australian artist and had once spent a year in Hollywood working as a movie art director. My father worked as a writer, and on Bedarra Island nearly 30 years later this man could tell a story about him that I recognized as remarkably accurate.

There were many curious and soothing things about Bedarra’s longest running beachcomber – most prominent among them a lovely sense of a life fully lived, which left him with an easy, humorous and entirely unselfconscious manner. He had been celebrated as a young painter when he first came with his wife – pregnant then with their first child…

He, himself, had left the island several times since first arriving in 1936, looking for better and different worlds, but always came back. His gardens, running up to the top of the hill behind the beach, were the focus of his life now and seemed to sustain him…

This day the house was filled with paintings his daughter had brought from Queensland to show him. Her name was Ann and her paintings were very realistic portraits of ordinary people and, I thought, excellent…

The beachcomber’s long absences, the years in Ireland and Hollywood and all his travel had given him the easy sophistication that his island neighbours lacked….

Sometimes Deanna Conti came over watched [VCR movies] with him. Bruce Arthur, a mile away, hadn’t been to Bedarra for a year. “Island politics are crazy,” the beachcomber said with amusement. “It’s like any small community. So-and-so won’t talk to you because you talked to so-and-so.” …

He was a charming and funny storyteller and had me laughing much of the time. Under it though was a well-defined and quite sober philosophic attitude that valued the utilitarian over the representational (“I find art a little silly now,” he said), the present tense over any other and invoked a rather strict humility as well. His life, he seemed to be saying, was in the absolute now and not open for interpretation.

I asked him if he thought of writing about his life, and he said, “don’t want to leave anything behind, have nothing to sell. I don’t even want to be remembered.”

In the 80s, the pressure from tourists staying on the island became intolerable and the cost of rates on Bedarra escalated making it difficult for Noel to make ends meet. He was persuaded by real estate agents to subdivide his land into seven group title allotments which he sold, retaining only his home and land on Doorila Cove.

Eventually, the noise and presence of residents building nearby became too much and Noel sold up and settled on the mainland on the Atherton Tablelands in 1996. He was then 84 years old, and his health was deteriorating. He developed a liver condition and became quite unhappy in the last stages of his life. He lived in four different locations in North Queensland, thereafter, always seeking solitude and the ability to live his life on his own terms.

Noel Wood on Bedarra 1980, on his home beach, Doorila Cove.

Peggy MacIntyre was a fan of the man and the artist and said:[1] One of the nicest things about him is that he is a human being, with a sense of humour; and a whole-hearted admiration for the works of other artists.

Steve Kenyon and his wife Jenny lived on Bedarra for two years and knew Noel well. Steve wrote a small collection of Noel’s thoughts and sayings in his book, Heaven is within you: Reflections from a beachcomber’s mind.[2] Steve says in his notes on the author that he travelled extensively, always seeking unique characters. However the most priceless person lived right here in Australia ... Noel Wood.

We learn from Steve that Noel was always, immersed in nature and that his thinking was based on Eastern philosophies such as Zen Buddhism. Steve’s quotes indicate that Noel lived in the moment without regard for the past or the future: This is what counts, the here and now. He lived by the Buddhist ideal to live simply and not acquire things and to sustain yourself by growing your own food. As he said repeatedly to the press, The hermit is not lonely, but he is alone. He saw all as ephemeral and The only permanence is change.

Many people in this world talk much of their personal philosophies of life and tend to chide others for not living that way. Noel Wood, from all that is written of him, appears to have had a clear and articulated philosophy and to have lived it throughout his years on Earth. He was true to his life ethics and did not plead with others to follow his lead.

On love he cited, Love is where you are, Love what you are doing, Love whom is with you. He also liked Aldus Huxley’s view … try to be a little kinder.

He wasn’t an ordinary person, Noel. He was very kind to people, very sweet. But he never really loved a person, or an animal. What he really loved was his island and his painting.

Eulogy, Ann Grocott.

NOEL RECOGNISED

Independent art curator, Gavin Wilson, worked with the Cairns Art Gallery to create a successful exhibition aptly named, Escape Artists: Modernists of the Tropics. This was the first exhibition by the gallery to tour nationally (1998 and 1999) and it featured 24 artists who had escaped life in big cities to create their works in North Queensland. Among the artists chosen to be exhibited were some of our district’s most notable artists: Noel Wood, Yvonne Cohen, and Valerie Albiston.

In his catalogue, Gavin Wilson spoke of their art:[1]

Noel Wood’s Dunk Island c. 1946 and Yvonne Cohen’s Mango Trees 1945, both exhibit a passion for the pure use of colour. This direct intuitive approach reveals an affinity for the work of the Fauves. But the great difference between the two artists is temperament. There is an edge to Wood’s work. ... One gets the impression that in all this profusion of life and apparent sense of freedom, is a doubting, troubled individual.

On the other hand, Yvonne Cohen displays a bright optimistic temperament that revels in the elements on offer. Her vigorous use of colour reflects the joy of living in the most idyllic of circumstances. Cohen’s effective use of colour prevents the work from tottering into the facile. In the best of Valerie Albiston’s painting we see a reductive process at work. Albiston shows an interest in cubism, particularly the work of George Braque. Her probing, analytical approach to the problem of eliciting meaning from the tropical landscape, as in Timana Island, 1945, derives from her skill in deploying line and mass all within a narrow colour range.

In short, Wilson rated these three artists highly enough to place them alongside some of Australia’s most renowned artists in this key exhibition.

Exhibitions in Townsville (2013), and Cairns (2014), named To the Islands were curated by Ross Searle of the Perc Tucker Regional Gallery and featured works by Yvonne Cohen, Noel Wood, Valerie Albiston, Fred Williams and Deanna Conti with one by Roy Dalgarno and one by Fred Williams and Bruce Arthur.

Shane Fitzgerald, project manager for the exhibition, commented in the catalogue:[2]

Little has been celebrated of these artists over the years yet their impact on Australian art still resonates today. Many notable practitioners visited the idyllic and remote Dunk, Bedarra and Timana Islands over the years …

Curator of the exhibition, Ross Searle, added:

While not all of the artists associated with this exhibition are household names, they produced highly original works of art in what is a little known period of Australian art history. … the creative energy of Wood, Cohen, Albiston and Conti remains unparalleled and little appreciated in the national context. For decades these artists produced strikingly original works of art. … indeed the work of Noel Wood and the Cohen sisters is quite remarkable and their reputations as pioneers of the Modernist Australian painting movement remain underappreciated. There continues to be a wholesale underappreciation of regional artists to the overall canon of Australian art. At the time of Noel Wood’s most active period in the 1940s and 50s, he was the first artist in Australia to establish a national profile from a regional base.

In 2017, Noel Wood was recognized with an article in the Financial Review written by Steve Meacham.[3] Steve started by saying:

Hardly anyone recalls Noel Wood today. Though his works are in the National Gallery of Australia’s Collections – and in several other State galleries around the nation. Art commentators accept that he was the first “fine artist” to paint North Queensland’s lush, tropical coast with critical success – decades before Ray Crooke settled in Cairns. Yet Wood’s celebrity (and he was a frequent subject of newspaper and magazine stories from the 1930s until the 1980s, culminating in a 1987 ABC documentary favourably reviewed by Anna Murdoch, then wife of Rupert) was based on his eccentric lifestyle as much as his art.

Glenn R. Cooke, once curator of the Queensland Art Gallery, has the last word on Noel’s art:[4]

Wood was probably the most recognized artist in Australia at that time. … Wood was the only artist of the 20th century who established his national profile from a regional base and remained the most prominent artist to live in North Queensland until Ray Crooke settled in Cairns some thirty years later.

Noel WOOD/Australia 1912-2001/ Two boats 1946/ Oil on canvas/ 45.7 x 56.5cm/ Purchased 1946/

Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art/ © QAGOMA/ Photograph Natasha Harth, QAGOMA.

ANN GROCOTT COLLECTIONS

A true understanding of who Noel Wood was as a person and an artist is best gleaned from some descriptions and stories of him, generously shared by his younger daughter, Ann. In 1964, after living for 26 years estranged from her father, Ann was visiting Tully when on leave from work in PNG with her first husband, Tony and she reached out to Noel and offered her love and forgiveness. Noel accepted this kind gesture. Ann, Tony and their two children visited Bedarra shortly after and father and daughter were reunited thereafter.

Ann and her husband started to stay on Bedarra at Noel’s guesthouse and from then on they met often and shared their life stories and when Ann remarried she and her second husband, Terry visited Noel as well.

Rather than melding Ann’s recollections in with the research from newspapers and other records and the memories of others, the memoirs provided by Ann, mainly as emails, are recorded here separately. That generates a little repetition, yet that is perhaps a small price to pay for the richness of the personal insights provided by Ann.

Ann’s life is briefly outlined later in this publication but suffice to say that at this point that she was a published author before she achieved so much as an artist. These are her unique recollections of the life and art of her father, Noel Wood.

Noel WOOD, Working Horses, SA c. 1930, private collection.

BEFORE BEDARRA - ANN GROCOTT

I found my memory was still very good in my seventies but, like the body, started to go downhill after 75 and now, in my 80s, it either lies completely doggo or behaves capricious as an imp. Dad had a photographic memory (despite – or perhaps because of – his drinking), but I still remember much.

Mum had much to do with arranging his first exhibitions in Adelaide and attracted notable people (who she had been to school with) to open his shows and she paid for all his art needs. She had been a boarder at Girton and knew the right people to open the exhibitions and to invite with a view to sales. Earlier, she herself had a couple of successful exhibitions (I was told this by an old friend she was at Art school with). She gave up her own painting because she thought Noel had the greater talent; maybe he told her that. Dad painted a portrait of Mum while they were on Kangaroo Island.

EARLY BEDARRA DAYS

Late in 1936, my parents had reached Tully in their old Model T Ford and were at the bar of the Tully Pub, telling the drinkers they were looking for an island to buy when someone mentioned that Jack Harris was selling land on Bedarra. A fisherman called Nugget took Dad there (Mum being heavily pregnant) and Nugget told Dad that, due to the tides, he had only half an hour to make up his mind. As soon as Dad ascertained there was a freshwater spring, he decided he wanted it.

My mother paid the entire £45 for the 15 acres. The title deed, in both their names, is written by hand and dated 24 December 1936. I found it in the solicitor’s office hanging on the wall. There is an add-on from 1938 in different writing, about the conditions mentioned signed by a couple called named Coleman. This couple were called Mr and Mrs Crusoe in an article in the Sunday Mail, 01 January 1939 and must have been neighbours because the article has a picture of Dad up a tree. (Scribe: The Colemans purchased the remainder of the island, but not Noel’s 15-acre lot.)

Baby Ann Wood with father, Noel, on Bedarra C. 1939.

I was conceived on Bedarra Island and the only photo of me there is as a tiny child standing, naked, with a hat on, next to my seated father who has put a whole lot of bananas in my cut-down pram. I don’t know anything about them living in a tent when they first went to Bedarra, but I know the first dwelling they had was a grass hut built by Dad. Mum, baby Virginia and Dad lived in the grass hut while Dad built our house. The house he subsequently built himself on Bedarra was my favourite house in the entire world and I often think of it. It was known as the House of Singing Bamboo.

Bedarra Title Deed, Noel and Eleanor Wood, 1936.

Bedarra Title Deed, Noel and Eleanor Wood, 1936.

The house had a feature wall from bottles of rum, whisky, gin, and champagne consumed on the premises. The sun shone through that bottle wall like they were stained glass windows. Dame Zara’s taste in gin led to many blue bottles on Noel’s famous wall.

Mum and Dad both worked on making the essential food gardens on Bedarra Island. There is no good soil on the islands, so they had to bring up seaweed from the beaches and add ashes from the open fire, which is where they cooked their food. To demonstrate the poor soil, Dad once showed me a small native bush that came up to my thigh. This has only grown 3 inches in 40 years, he said. It is such a credit to him that his gardens grew lush fruits, vegetables, and bamboo.

He only had to go to the mainland for liquor which, when poor, was bought as cheaply as possible and brought back in bulk containers. When he had money he drank the best champagne, brandy etc. and, on his only visit to me in Bundaberg was appalled to learn I had never tasted Krug – so I drove him to wine merchants until we found the only bottle of Krug in Bundaberg, which cost a fortune, but he bought it and we drank it together.

After women and children were told to evacuate from Australia’s tropical islands (in 1940) due to a sighting of enemy ships, Mum and the two kids first waited on Dunk Island to be taken to the mainland. Noel was supposed to stay and grow fruit for the troops. We lived in the tiny Victorian town of Woodend where Dad visited us once. I have noticed that Dad’s family were never mentioned in the Press again – more exciting to have a good-looking single painter on an island, I suppose. Mum used to order paints to be sent to him (and paid for them). Dad sent us slices of mango, dried in the sun, and soaked in rum (yummy!) Each slice was packed between leaves. He mentioned to the Press that he had a family when I began to be written about for my writing and painting.

I have loads of old cuttings about Dad, including a print of one from The New Yorker – 26 May 1956 – called Bach and Bananas. I have two interesting newspaper clippings written by my mother, about living on the island. One is from The Forerunner, called Bedarra and dated May 1937. The other, which has photographs, is from The Advertiser, Adelaide, called Summer Comes to Bedarra – Idyllic Life on Queensland Tropic Isle dated 12 November 1937.

NOEL | DAD

Dad was resourceful, a voracious reader, a great cook, and wasn’t concerned about leading a regular life. The island was his paradise, his bolthole, he knew every inch of it, and he loved it.

He talked about Yvonne and Valerie Cohen and mentioned giving them art lessons. He often stayed on Timana with them. He remembered Valerie saying to him: You are like a piece of driftwood brought here by the tide, amongst the other flotsam and jetsam … you let the sea take you here and there. I sort of understand what she was trying to say as Dad came from another dimension, he lived in an eternal present and was very charming to all, but he was a visitor, which I suppose was why he wanted an island of my own.