Author: Helen Pedley

Editors: Leonard Andy, Dr Valerie Boll & Ken Gray

|

Abridged Story |  |

Full Story |

Written European records are one-sided, but the observations that we have, do give glimpses of aboriginal lifestyles at the time of contact and soon after. These reflect the traditions of the observing writers and may only be based on superficial contact.

They are inadequate and often in an inappropriate style, but they are what we have. The first navigators along the coast kept logs and journals; the bêche-de-mer fishers and the cedar-getters did not, but soon reports were appearing in newspapers which can yield information of interest. Reports to Government officers, are of interest as well.

Later, Banfield provided his view of the story. A much later report on this settlement collected some oral histories from Aboriginal people regarding the events of that time. Ideally, more such oral histories and memories from Djiru people would balance the current work.

SURVEY SHIPS

Cook’s Endeavour was sighted by Djiru people when it sailed past on 8th June 1770. Joseph Banks, wrote in his journal the same day, that the mainland “by the number of fires seemed to be better peopled. In the morning, we passed within ¼ of a mile of a small islet or rock on which we saw with our glasses about 30 men, women and children standing all together and looking attentively at us”.

The armed brig Kangaroo, from Port Jackson for Ceylon, commanded by Lt. Jeffreys, in 1815 followed Cook’s track within the reef. At Cape Sandwich, he “had communication with the natives, who were very friendly and conveyed fruits to the vessel”.

Captain Philip Parker King made several voyages in these seas. In 1819 he sailed the Mermaid on an exploratory voyage to the northern waters. He named Goold Island and recorded his meeting with the indigenous people. These people were most probably not Djiru. The Aboriginal people seemed not at all overawed. In the evening some of King’s officers visited the camp ashore and were peaceably received by the men, the women having been previously sent across the island.

Captain Blackwood carried out surveys on the Fly in 1843 with Bramble as her tender. Geologist Joseph Beete Jukes found the people “friendly and familiar at first”. However, on the last night, the fishing party took a good haul of fish in the seine which they shared with the natives who suddenly attacked the party. One of the attackers was shot and the attack ceased. Also, while Jukes and two men were in a creek on the north side of the bay, they were surrounded by 40 or 50 locals who pelted them with basalt blocks. The assailants were “discouraged by a charge of No. 4 shot”. Perhaps they became less friendly because the intruders had taken a lot of fish without permission.

THE KENNEDY EXPEDITION AND THE 1848 MARITIME SURVEYS

Edmund Kennedy was appointed to lead an expedition in May 1848, projected to land at Rockingham Bay, from there to traverse Cape York Peninsula. These men were to be the first white explorers to spend more than a brief time on Djiru country.

Kennedy’s contact at Rockingham Bay seems to have been peaceful. Carron, a member of the Kennedy party, wrote that after he had examined the artefacts found in the “gunyahs”, he “left them where I found them”, an attitude which the Aboriginal owners would have noticed. White people who came across Aboriginal camps in later years frequently helped themselves to whatever they found, including mortuary items.

Dixon was told by Dyirbal Elders that at first, the white-skinned visitors were believed to be the returned spirits of their ancestors. They were not thought to be a threat. “By the time we found out this was not so… it was too late for the Englishmen had taken advantage of our goodwill”.

THE BÊCHE-DE-MER INDUSTRY

The bêche-de-mer industry brought early external contact to the Djiru people. Johnstone described the process of bêche-de-mer fishing as follows. A Captain would fit out his boat, “secure” his crew, and then proceed to an island to establish a camp and build a shed (smokehouse). “Securing” a crew often involved kidnapping Aboriginal people. To engage cheap labour, in some cases, the captains offered flour, tobacco, sugar, tea or alcohol to the Elders at Aboriginal camps. Elsewhere, men were kidnapped, as were women. Sex was involved in recruiting and “venereal disease was rampant”.

The industry was largely unregulated. Meston noted in his 1896 report, that while some crews were treated fairly, others were enticed aboard, made to work like slaves, then shot, marooned on the reef or landed far from their own homes. The bêche-de-mer men would occasionally be killed by their Aboriginal crew in retribution, or at least abandoned when the crew secretly left. The operators would also kidnap women from Aboriginal camps, sometimes leaving “a legacy of disease as well as demoralisation”. Parry-Okeden said the bêche-de-mer fishers were “the lowest of the low”, wielding absolute power at the lonely fishing stations. He had no doubt that they cruelly wronged and oppressed the Aboriginal people working for them and thereby provoked the so-called “atrocities”.

In the Mission Beach region, bêche-de-mer stations were known on Dunk Island by the early 1870s. Steve Illich (Illedge) was a Portuguese from East Timor who had been a timber-getter in the beaches area. He made a home on Stephens Island, in the 1880s. From here he carried out bêche-de-mer fishing. He had huts there for his Aboriginal labourers, smokehouses for drying the catch, and a fleet of six boats. He also had a house for his Timorese wife and their children. However, the cyclone of 1890 put an end to his enterprise. He then lived on the mainland at Murdering Point. His granddaughters Grace and Biddy, being of Aboriginal descent, were later sent to Palm Island, as also subsequently was his son Andrew.

There were many reports of Aboriginal people being taken from the area to be labourers on the pearling and bêche-de-mer boats. In 1903, officials thought there were 500-600 mainland Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders engaged in the trepang and pearl fisheries of northern Queensland.

Writing in 1899, Roth as “Northern Protector” noted that employment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on the trepang and pearling boats was detrimental to the indigenous population in that a high mortality was found among the young males engaged as crew. Contact with the bêche-de-mer fishermen brought in diseases to the tribes. Also, minor ailments that afflicted Europeans and Asians were contracted by the Aborigines, but as they had no immunity, due to “want of proper care and nourishment” the effects of these ailments were “not so transitory”.

Djiru encounters with the bêche-de-mer fishers ranged from the unpleasant to the horrendous and ultimately fatal. While the numbers of consequent deaths on either side may not have been huge, they were significant.

CARDWELL – PERMANENT EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT

The Djiru first experienced contact with Europeans who were passing through, carrying out surveys, or kidnapping people. The establishment of Cardwell in 1864 brought permanent settlers to the region. As more settlers arrived, taking over Girramay and Jirrbal land, they also brought conflict. The Aboriginal people who were being dispossessed of their country retaliated and the white people demanded protection, so the Native Police Troopers followed. Conflict situations lead to reprisals. It was only a matter of time before Djiru country was also the object of encroaching selection. However, before this, an unfortunate and tragic series of events unfolded with the wreck of the brig Maria.

THE WRECK OF THE MARIA

The incidents that took place on the coast following the wreck of the brig Maria in 1872 became widely known and notorious at the time, with reports appearing in numerous newspapers. The episode and aftermath are still discussed in the literature today.

The Maria, a barely seaworthy vessel, left Sydney in January 1872, carrying a gold prospecting expedition consisting of 75 men, bound for New Guinea. She ran into gale-force winds and struck Bramble Reef on February 26. The ship carried a reasonably good boat that the Captain commandeered with six of the crew as oarsmen. Two other leaky boats would not hold all the remaining men, so they made rafts from the ship’s timbers. When the Maria went down some men drowned.

The 28 men in the two smaller boats ultimately made their way to Cardwell via Hinchinbrook Island and told their story. The Tinonee was chartered to search for other survivors, but none was found. Then two exhausted survivors from the Captain’s boat arrived at Cardwell on March 6. Their party had been attacked by Aboriginal people soon after their boat made land, the Captain and two others had been killed but these two had escaped and worked their way to Cardwell, travelling mainly at night. The remaining two from the Captain’s boat arrived in Cardwell a day later. Midshipman Sabben of the Peri, then lying at Cardwell under the charge of Captain Moresby of the Basilisk, was sent to locate the Captain’s boat; the men were well-armed. It was found near Tam O’Shanter Point. As they removed the boat, the men were attacked by 120 “hostile natives” who threw a volley of spears, none of which struck any of the party. Sabben’s men opened fire at 80 yards. Eight Djiru were killed and eight lay wounded when they ran to safety. Hayter later stated the attackers numbered about 200 which perhaps demonstrates how the story was already evolving.

Survivor of the large raft, Ingham, was to recall that a search was made of Tam O’Shanter Point where the Captain’s skull was “found in the blacks’ camp and was identified by his artificial teeth. His remains and those of the men who were killed by the blacks… had evidently been eaten, for Sub-Inspector Johnstone found dillybags in a native hut containing pieces of partly roasted human flesh”. Whether or not this was true, or if the bodies of the Captain and the other two men “were never found” such claims fuelled the fears of the settlers and increased their calls for reprisals.

Sometime later, a rusted rifle barrel was found on the beach near Tam O’Shanter Point by Banfield. Thinking it could be a relic from the Maria wreck, Banfield wrote to Lawrence Hargrave, who had survived the wreck by getting to Hinchinbrook Island and then to Cardwell. Mr Hargrave replied to Banfield, agreeing the rifle barrel would be “the one that Captain Stratman fired on the blacks with and brought about the deaths of himself and some of the boat’s crew”.

Following Sabben’s report of the attack when they sought to remove Stratman’s boat, Police Magistrate Sheridan at Cardwell requested Captain Moresby’s assistance to take necessary action following the acts of violence and murders committed by “the blacks” to ensure the coast would be safe. Moresby commanded Lt. Hayter to take the Peri with a crew of fourteen to transport Sub-Inspector Johnstone and his Native Police troopers to the scene. A second boat accompanied them, crewed by volunteers from Cardwell. Moresby felt the step was painful but necessary. Hayter was instructed “to punish the Blacks for their murder and attack on the boats’ crew”. When Moresby wrote his account published in 1876, he said “I felt it painful to take such a step… necessary not only for the sake of justice and in the interests of all white men who might hereafter be placed at the mercy of the tribe, but to secure the safety of Cardwell itself”.

The Peri firstly anchored off Dunk Island. The native police troopers walked around the island in two groups. Hayter and Johnstone found only deserted camps and canoes, which they destroyed, but heard a number of shots. Crompton, in charge of the second group, later told Hayter there had been only “a very few blacks” on the Island and that the main body was on the Mainland. If this account reconciles with Gowlland’s information (recorded in his journal) that Johnstone’s troopers had accounted for 16 Aboriginal people on Dunk, then Crompton clearly thought 16 was “very few”.

On the mainland according to Moresby, “the tribe was surprised before daylight, several unfortunate blacks were shot down by the native troopers, who showed an unrestrained ferocity that disgusted our officers; and the camp, in which some of the effects of the four murdered men were found was destroyed.” Hayter’s party “heard firing and saw a tremendous column of thick black smoke about a mile up the coast so we knew pretty well what had happened.” He arrived at the burnt-out camp and found a large quantity of the men’s effects (revolvers, trousers, etc.) as well as “a lot of human bones that had been burnt but whether of white or black men it was impossible to say”. Hayter took a native boy back to Cardwell; he was about six and his father had been shot. “He became a great favourite on the Basilisk but died in England of disease of the lungs”.

Hayter’s men continued to burn all the camps they came across as they continued south to Tam O’Shanter Point. The troopers then told Hayter they were watching a large camp at the Hull River with about 100 “fighting men” but when they went to attack, they “couldn’t find the camp and the party only came across four or five Blacks who had been constructing a canoe to cross the Hull and watch the schooner. Three of them were shot and the Gin taken prisoner. She deliberately threw her child in the river, I was told, when she saw the party coming”. Hayter then returned to Cardwell.

Meanwhile, the search for survivors continued in the Basilisk under Captain Moresby’s command. North of the Johnstone River mouth, eight emaciated men were found on 12 March, the survivors of the thirteen who had embarked on the larger raft. The friendly disposition of the tribe they had encountered (probably Wanyurr people), had ensured their survival, as Forster later described. The second raft was found south of a river that Moresby named “Gladys” (Johnstone River), but only two bodies and no survivors were found there. A few miles south another body was located, apparently killed by the locals. A later search by Lt. Gowlland of HMS Governor Blackall accompanied by Robert Johnstone and his troopers, located six more bodies further south. Three were in the vicinity of the “Louisa” River mouth (Maria Creek). The men were probably trying to walk to Cardwell but had been killed. All but one of the corpses had had their skulls smashed, probably by a rock.

Gowlland had been instructed to take the Governor Blackall from Sydney to the area to search for survivors. In his report he stated he had requested the assistance of Mr Johnstone and his detachment of native police. “Every native camp between Cardwell and Point Cooper, a distance of some fifty miles, was visited and minutely searched for any traces of white men...”. His diary also records that following the discovery of the final three bodies, Johnstone and his troopers “surprised a large camp of natives … Mr Johnstone’s trackers shot 27 Blacks in this camp”.

As well as burning all the camps they found along the coast during their search, while the Governor Blackall was anchored under Brook Island, Johnstone was instructed to land at Hull River and “examine the two large blacks’ camps there indicated by immense hunting fires”. Gowlland then proceeded to Dunk Island to take on water. He noted they saw tracks but thought they would be “gins” as “Mr Johnstone and his trackers having given a very good account of the 16 he came across”.

In Johnstone’s official report that accompanied Gowlland’s report, he stated, “I have severely punished the guilty parties.” Johnstone’s actions on carrying out this punishment were noted in a country newspaper article claiming also that Johnstone spoke of killing whole camps, including women and children, with the greatest coolness. The matter was brought up in the Queensland Parliament as it reflected on the policy of the Queensland Government and was an atrocious libel. Johnstone denied the charges. The people of Cardwell thanked him for his “exertions throughout the late sad catastrophe” in a signed testimonial that subsequently was displayed in the Shire Hall of the Johnstone Shire, a shire named in his honour which no longer exists.

The police carried Snider rifles; “they made a hole in a human body as large as a twenty-cent piece”. Rifles do not have great advantages over spears in the scrub, but on the beach they are supreme.

Richards, in his work “The Secret War”, concludes that in Queensland, the Native Police played a major role in the dispossession of the Aboriginal people of their land, the almost complete destruction of Aboriginal law, and the disintegration of Aboriginal families. The task of the Native Police on the frontier was to immediately and brutally suppress any Indigenous resistance to European colonisation. Their business was “dispersal” of the Aboriginal people who resisted the colonists.

During the Maria reprisals, all Aboriginal people apprehended in the ensuing searches were shot, including, probably, those who helped one group of survivors. “There can be no doubt that the Native Police on this occasion operated in a retaliatory fashion … The indiscriminate slaughter of Aboriginal people, for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, decimated some local groups.

Bottoms, in “The Conspiracy of Silence”, provides a review of Sub-inspector Johnstone’s work with his Native Police troopers, listing the killings he was responsible for, including the “punitive raids” he led following the wreck of the Maria. While eleven white survivors of the disaster were killed by local Aboriginal people, the retaliatory action resulted in what Bottoms estimates as a total of about 88 Aboriginal men, women and children being killed in response when camps were raided.

Others put the figure higher. Gray’s careful analysis of numbers in available reports concludes that between 113 and 140 Djiru died as a result of the Maria reprisals.

There is no doubt that many Djiru people died and those remaining were even less inclined towards friendliness. The settlers at Cardwell for years lived with anxiety about Aboriginal attacks even as they annexed land and debarred the original owners from their Country. Aboriginal resistance to this intrusion was persistent. The people of the Rockingham Bay hinterland became notorious as fiercely resistant, “the most murderous and war-like of any tribe in Northern Queensland” according to Johnstone writing about the murder of the crew of the Riser which struck King Reef in 1878.

CEDAR-GETTERS

Bêche-de-mer fishermen were soon followed by men intent on cutting the red cedar of the area. They trespassed on Djiru country, cutting trees and clearing tracks to haul the timber to the waterways for shipment out. They were also “avid sexual predators”, who took aboriginal women by force.

One writer declared, “they [cedar cutters] are the roughest of rough fellows, muscular as a working bullock, hairy as a chimpanzee, obstinate as a mule, simple as a child”, with a fondness for rum.

“Cedar-Getter” wrote from Clump Point that cedar there was good quality but very scarce, there not being more than 300,000 to 400,000 feet when all cut. “Timber Getter” observed that Mr Freshney’s bullocks were employed to draw timber down to the beach at Clump Point where “the soil here is superior to any in the North for sugar-growing, not excepting even the Herbert River and there is plenty of good grassland”.

Timber merchant Charles Freshney, his son and his daughter-in-law died in December 1880 when their boat capsized in Hinchinbrook Channel following a sudden squall during a pleasure trip. The “kanaka” on board survived by swimming to shore.

Although the cedar-getters were only temporary occupants of limited areas of Djiru country, as well as cutting down the red cedar trees, they cut tracks through the scrub for the bullock teams, destroying whatever was in the way and took over the best landing spots and tracks to the beach where the logs could be loaded and shipped. They also took over Djiru camping places near freshwater at the coast. They also shot wallabies, ducks, pigeons, scrub turkeys and helped themselves to the riches of the Djiru estate as their right.

They were strangers, and strangers should have asked permission or been invited as visiting tribal groups did through message sticks and exchange of artefacts and food items. It can only be surmised what forcible taking of Djiru women and children, and other abuses took place. What is known is that Djiru people continued to attack white men straying onto their country.

THE SETTLERS AT BINGIL BAY

Four brothers: James, Herbert, Leonard and Sidney Cutten, rowed up the coast from the Tully River scouting for property to select. They liked the Clump Point area but Hyne had already made his application. However, in 1885 they made a successful application for the Bingil Bay property they soon called “Bicton”. They planted every kind of citrus tree, tea, coffee, coconuts, tobacco and pineapples.

They employed Aboriginal labourers, Malays and South Sea Islanders (“Kanakas”). There were cottages for the latter, while the Aboriginal people “had their own grass gunyas”. At times they had as many as 50 Aboriginal workers but on average there were 10.

The move to employment by the white people occupying their country, as well as the introduction of Pacific Islanders, must have required more major adjustments by the Djiru. There were allegations of Kanakas taking Aboriginal women by force. Robert Johnstone, as manager of the Bellenden Plains property, wrote in 1871 of regular fights between the Kanakas and the local Aboriginal groups.

The Aboriginal people working for the Cuttens had perhaps come to a forced compromise. In order to remain on their own country, the men worked, giving them access to European food and goods, which had become attractive, such as flour, steel “tommyhawks”, metal fishhooks, tea and sugar.

Those Djiru who signed up to work were not likely to be rounded up by the troopers and removed to a mission such as Yarrabah. Provided tracts of their country remained undisturbed, the women and some older people who were not employed could continue to forage for food for those living in the camps. However, clearing and felling of timber continued to reduce available sources of food. A one-off allotment of flour and tobacco could never compensate for the loss of vital food trees.

THE OPIUM ISSUE

The Chinese came to Queensland originally to the goldfields, in this region, particularly to the Palmer River. As the goldfields declined, the Chinese moved down the coast, some arriving in Djiru Country to grow bananas successfully where Europeans failed. They also ran stores. Before the importation of opium was prohibited, “practically all the Chinese merchants carried the drug [opium] as a legitimate line of merchandise”. The Chinese found the opium charcoal useful cheap payment for both Aboriginal and Pacific Islander labourers.

The problem of opium use and abuse was a contributor to the passing of the notorious 1897 Act that was devised ostensibly to “protect” the Aborigines of Queensland, and directly led to the Government’s Hull River Aboriginal Settlement.

In 1902, the numbers of starving Aboriginal people, unable to gather food on their traditional lands, had increased and just over £60-worth of rations was distributed monthly at an average of 21 relieving centres. The Djiru people at the Cutten camp, however, were not deemed to qualify.

On the one hand, the payment of wages “under agreement” (under the 1897 Act) involved payment into an Aboriginal employee’s bank account that was overseen by the local Police Officer in the towns of Geraldton or Cardwell, which was legal but demeaning. On the other hand, avoiding this on the grounds of difficult logistics and paying with rum or opium was not acceptable either.

THE POLITICAL SETTING

The political context and government thinking and policy regarding the Aboriginal population of Queensland affected Djiru people, particularly with the enactment and implementation of the 1897 Act for the Protection of Aborigines. The philosophy of paternalistic protection on the cheap underpinned this legislation, which provided the power to forcibly remove people to reserves.

Archibald Meston as Special Commissioner, undertook to report on the Aborigines of North Queensland with a view to proposing a scheme for their so-called ‘improvement’. His report recommended the maintenance of reserves for their protection.

In 1897 the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act became law, with additional clauses enacted in 1901. Under this legislation Aboriginal people were not allowed to drink alcohol, or to marry a white person or to keep their own savings bank book, which had to be kept by the local policeman. The leading police officer in each district was delegated local ‘Protector of Aboriginals’, most of whom now became wards of the state. Aboriginal reserves became strictly monitored areas, with public access denied, and to which Aboriginal people under the Act could be forcibly transferred.

Aboriginal people called this Act “the Dog Act” because they were treated like dogs.

HULL RIVER QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT ABORIGINAL SETTLEMENT

Meston’s concept of a Government Reserve on the northern coast was accepted. Continuing complaints from settlers led Chief Protector Howard to recommend, in his annual report for 1910, that a settlement be established in the Tully River district. His official tour the following year included two visits to the proposed site at Hull River.

At this time there was little understanding of the relationship between Aboriginal people and the country where they lived (and certainly no concept of aboriginal ownership). Foxton’s report to the Governor of Queensland included this comment: it is claimed by “men who have had life-long experience of aboriginals that the latter cannot be transferred from one district to another, as suggested, with satisfactory results. It is said that they fret and pine for their old haunts and surroundings, and if too far away to enable them to return they are apt to become restive and rebellious, and a source of danger to those about them.” His solution was instead of moving just a few, to transfer them all.

Prior to the Hull River Settlement, Aboriginal people were forcibly removed from the area. But when Hull River was opened, wholesale forced removals to the Settlement commenced. Forced moves were the cornerstone of the reserves, keeping Aboriginal people in one place, away from white settlers.

Banfield wrote that when the Settlement was definitely going to eventuate, “most of the blacks in the immediate neighbourhood disappeared” a result of their dreadful past experience of measures by ‘big fella Gubberment’ and rumours it would be a prison (put about by the Chinese and others). They also knew rum and opium would not be allowed at the Settlement.

The appointed superintendent, John Martin Kenny, a former officer in the Native Police at Cooktown, arrived at the selected site in 1914. Those indigenous people who knew of the Settlement were ‘in great dread’ of the scheme, but by the end of the year 41 Aboriginal people “had mustered up courage to join”. Of these, 21 were people removed from Clump Point.

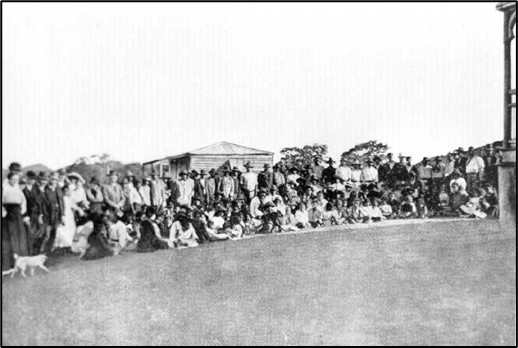

Aboriginal people at the Hull River Government Settlement, c.1916 (Chief Protector’s Annual Report)

People continued to be taken to the Settlement, but available records indicate they were from the wider Murray River area as well as from further afield including Charters Towers, Bowen and Townsville. Jirrbal and Girramay people fled to the rainforested mountain areas rather than become inmates at Hull River, of whom there were 400 in 1915, with a further 82 added in 1916. Deserters, if caught, were returned through Cardwell by sea, often also spending time in the watch house awaiting a boat.

Recounted memories of the life reveal the rations were sparse and the people supplemented them with hunting, but there were a lot of people and only a small area where they could hunt. The 1917 Annual Report sates: “the fishing boats did much towards providing supplies of fish, turtle, dugong, oysters, etc. to meet the scarcity of beef”.

Chloe Grant’s memories of the Settlement (passed on to her son, Ernie) were also of too many people in one place and not enough rations. The old people were not happy, they hadn’t wanted to be there and some of them had been rounded up and taken there in chains. Chloe had worked as a maid for the Superintendent and spoke kindly of him and his daughter, but Ernie’s Uncles Willie and David, also told how he flogged Tommy Brook with an axe handle. They ran away soon after that. Chloe was about 15 when the cyclone hit; she was very shocked by it. She told how she ran away with some older people. They ran all night; the old people were very scared and insisted the kids travel in silence. They made it to Balara waterhole, where there was plenty of fish and other food to find.

It was on 10 March 1918, that the devastating cyclone destroyed the Hull River Settlement. The huts and humpies along the beach were demolished, as were the buildings. Superintendent Kenny and his daughter died during the destruction. There is disagreement over how many people died in total. Doctor Leary reported 9 deaths while the Chief Protector reported there were 12 dead as a result of the cyclone. Others asserted some two hundred were buried along the sand ridge, with coral heaped over the graves. The graves were pointed out to Ernie Grant in 1944, “down on the flat”. The graves of those who died in an earlier fever epidemic at the Settlement were also there.

The Hull River Settlement was never rebuilt in Djiru country. Instead, a new station on Palm Island was commenced, conveniently off the coast where inmates could not escape as they had often done, disappearing into the bush surrounding the Hull River site. Removals to Palm Island commenced in June 1918 with those who had stayed at the Settlement. Others who had taken to the bush were also rounded up by the police. From then, and for many years afterwards, police patrols continued to apprehend Aboriginal people in the Cardwell district and send them to Palm Island. The people lived in fear of being caught. Yet there always remained some who either worked for the white employers or who survived in their own country by moving camp frequently, keeping one step ahead of the police. These people retained much of their cultural heritage, passing it on to their children.

There is now a memorial at South Mission Beach to the people who were taken to the Settlement, where some of their stories can be read. John Andy’s grandmother and her sister (Djiru people) were sent there. They ran away, crossing the mouth of the Hull River and walking south. They “deliberately walked in the water along the beach to ensure they didn’t leave behind any tracks, as they were afraid of being tracked down and sent back to the Settlement by the police”.

Leonard Andy, Djiru Traditional Owner, said of the Hull River site (now South Mission Beach), “for our people it was an extremely sad place and always will be.” The memories are all bad, and people don’t want to go there now. It will not be forgotten how deserters from the Settlement were severely punished or even murdered. Men were cut at the back of the leg so they could not run away again.

DISEASES AND HEALTH

It is unquestionable that the diseases and sicknesses that Europeans and Asians brought with them to the Australian land mass affected the indigenous people drastically. Lack of immunity to illnesses that affected the intruders only mildly, coupled with lack of treatment, malnutrition and the other evils of early contact situations resulted in numerous deaths as well as poor health and consequent misery.

Dr Roth observed in 1899 that the minor ailments that afflicted Europeans and Asians were often contracted by the Aborigines, but as they had no immunity, due to “want of proper care and nourishment” the effects of these ailments were “not so transitory” as they were for Europeans. In remarking that Dr Shorter reported that at Mount Garnet “the natives are reeking with syphilis, etc”.

Chief Protector J.W. Bleakley in his report for 1914, the first year after operations commenced at the settlement at the Hull River, advised that Superintendent Kenny “writes in strong terms of the terrible effect the opium traffic has had on the natives of this district. During the few years which have elapsed since the introduction of Asiatic races, what was once a huge population of fine, well-developed men and women has dwindled down to not more than a couple of hundred, the majority of whom are physical wrecks. It seems to have been a contest between the Asiatic and the low European for the right to exploit the aboriginal financially and morally, and, though the white man descended to the rum bottle and even to morphia, the Asiatic easily won with his deadly opium charcoal. The effects of some of these drugs on the poor aboriginal are appalling, producing aggravated constipation and eventually an agonizing death. Owing to the dense scrubs and bad roads, most of the surrounding districts are practically inaccessible, thus making detection of offenders a difficult if not impossible task.

Deaths at Hull River were listed as due to senile decay, venereal diseases, tuberculosis, pneumonia and malarial or coastal fever in 1916. According to Jones, but not listed in the official annual report, in February of 1917 malarial fever was found in the settlement and a medical officer ordered the Aboriginal huts to be removed from the swamps to higher ground. Jones records that some 200 people died at the settlement, possibly from this fever, measles or whooping cough. They were buried near the beach to the north of the shelter shed. Official correspondence reveals there were a number of deaths due to ‘fever’ in April and May of 1917 and the quarantining of the station on 2 April by Cardwell Shire Council on account of fever. Doctor Leary, Government Medical Officer, visited the settlement on a monthly basis and made a number of recommendations for improvements, including the erection of a jetty, the building of a hospital and the appointment of a nurse. The cyclone of early 1918 put paid to such improvements even if they had received approval.

Following the cyclone in 1918 and the end of the settlement, Banfield commented that some saw the Hull River Settlement as a means of “an extraordinary dissemination of malarial fever,” while “the graveyard on the seaside ridge tells its own story”.

We cannot know the number of Djiru who died at the Settlement as a result of illness, but there must have been many. They had already been decimated by the violent reprisals following the Maria wreck. Following the 1918 cyclone, the remaining people were transported to Palm Island.

In 2023, Traditional Owner Leonard Andy advised there were only 15 Djiru living on their traditional lands; most lived on Palm Island or Innisfail.

|

Abridged Story |